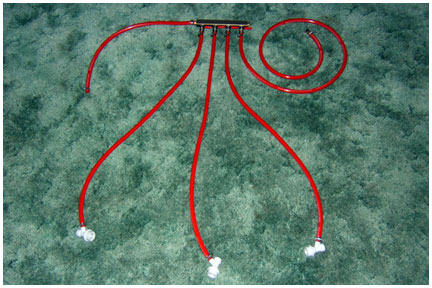

Gas Manifold

So I went to go hook-up my 4-way gas manifold in preparation of outwardly pimping my kegerator today.

Seems like all went well with setting up the manifold. I cut all my gas lines, one shorty coming in, three medium guys going out, and one biggie going out. The shorty supplies the gas for all four outgoing gas lines, the three medium guys go to the three kegs that will be in the kegerator, and the one biggie will be permanently hooked-up in preparation for use with another new toy, a Blichmann Beer Gun.

Unfortunately, after all went well setting up the manifold in preparation of switching over the tower to three taps and getting ready to fill a few bottles off the keg, things stopped going so well. I went to hook everything back up to the keg and gas first and pull a pint to make sure all went well. Turned on the gas, opened the valve on the regulator to let the gas out, opened the valve on the one gas line on the manifold to let the gas out, checked it was set to 10 psi, hooked it up to the keg and … nothing. No beer would come out. I lifted the keg and it felt pretty light, so I thought maybe I kicked it and didn’t realize it. Released the pressure on the keg, looked inside with a flash light, still like 3/4 to 1 gallon of beer. So now I have everything still hooked up with no beer coming out. Obviously I don’t want to fool with the Beer Gun until I get this in order.

To say this put a slight damper on my Saturday afternoon is an understatement. I really like the idea of having a kegerator, but I am not sure I am comfortable with the process of owning a kegerator yet. After homebrewing now for almost 9 years and having the idea of my own beer on tap be part of the whole grand scheme of things, and then to keep running into obstacles is extremely frustrating. I know I will figure it out, and I know it will be OK, but I just wish it wasn’t an issue in the first place.

Close-up of the gas manifold itself.Â

July 21st, 2008 at 10:01 am

themorningcall.com

High hopes for hops

Dan Weirback sows his own crop that will spice up his beer

By Tim Blangger

Of The Morning Call

July 21, 2008

Two things on Dan Weirback’s Lehigh County farm would puzzle most people. First, there’s his human-sized foosball court, a large-scale version of the tabletop soccer game. The court’s outline, formed by a series of fence posts, is near his refurbished farmhouse.

The second object is bigger, also involves gray fence posts — 91 in all — and covers an acre of land. Here, a few hundred yards from both the house and the foosball court Weirback, owner of the Easton-based Weyerbacher Brewing Co. is growing his own hops on a fairly large scale.

Although Weirback’s human-sized foosball court is unusual, his hops field is a rare commodity in Pennsylvania.

Among the tightly knit community of Pennsylvania commercial craft brewers, Weirback is alone in growing hops that he plans to use for commercial brewing. One other brewer with a Harrisburg-based brewery is growing hops on his own, and hopes to produce enough to use them in a batch, but his effort is still in the experimental stage.

Weirback’s first-year effort is an experiment, too, a learn-as-you-go exercise spurred by a sharp increase in the price of hops, a type of hemp that is a critical ingredient in making beer.

”Our first thought was that prices for hops have gone up 500 percent in a year or two,” says Weirback, standing among the rows of his first-year hops plants. ”In a year or two, I know the price will come down. Hops farmers are planting more fields. But I thought we’d give ourselves a little security for our hops supply. This should be worthwhile for us.”

About a decade ago, Weirback grew a few hops plants in his backyard, but he has never tried growing them on such a large scale. But the effort wasn’t totally successful. Those first hops plants did not produce any hops. He suspects he didn’t water them enough.

The effort hasn’t been cheap. In all, Weirback suspects he spent about $9,000 on the project, a figure that doesn’t include the labor of planting, weeding and maintaining the field.

Julia Herz, a spokeswoman for the Brewers Association, a national group that includes commercial craft brewers, says the practice of hop growing is increasing, although the association keeps no figures on brewers who grow their own.

”If they don’t already, more craft brewers should consider it,” says Herz. The Hops Growers of America, an industry group, keeps track of only large-scale hops growers.

Beer has four basic ingredients: water, malt, yeast and hops. The malt gives the beer its body and substance; the hops offers the spice. The spice is especially important to craft brewers such as Weirback, because the hops help differentiate craft brews from the less flavorful, mass-produced brews.

Most hops grown in the United States come from Washington State, Oregon or northern Idaho, where the cooler climate favors large-scale hops production. Other hops that craft brewers use are imported, often from Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium and Australia, among other hops-growing countries.

Hops once were grown along the eastern coast of the United States, as far south as North Carolina. Upstate New York, particularly the Cooperstown area, was a main hops growing region. But after an especially poor series of crops in the 1920s, when Eastern farmers encountered plant disease problems associated with the East’s humid climate, commercial production began shifting westward, according to Bill Bamka, a hops specialist with Rutgers University Cooperative Extension Service.

It’s still possible for Eastern farmers to grow hops, Bamka says. ”With most farmers, economics becomes the issue,” he says. To make money on the enterprise, farmers need to invest in very expensive hops-specific machinery, the kind used by commercial growers in the west.

Weirback first considered growing his own hops in the fall of 2007. It was actually his wife, Suzanne, who offered the suggestion.

Weirback started doing some Internet research and spoke with the extension agents at Rutgers who have grown varieties of hops as part of their experiments. The Rutgers agents said two types of hops, Centennial and Nugget, grew well in this region, so Weirback settled on those two types. Centennial Hops is a common ingredient in many Weyerbacher brews.

If Lehigh County farmers grew hops, which he suspects they did, Weirback hasn’t been able to find any record of it. He also spoke with hops growers who attended a recent craft brewers conference in San Diego.

The 25-acre hobby farm Weirback owns in the upper reaches of the county has about 15 acres for cultivation. Although a nearby farmer contract-plants wheat and soybeans on most of the land, Weirback marked off a slightly elevated, one-acre plot in the late winter and started work on his hops field.

Hops require a support or trellis system, so Weirback devised one using 12-foot poles, sunk about three feet into the ground. His plot has 13 rows, with the poles of each row connected with guide wires attached to the top and bottom of the poles.

From the upper and lower guide wires, Weirback attached dozens of small ropes, which would eventually support the growing hop vines.

Before planting, he also installed an automatic watering system, which is critical for hops. It applies a few drops of water every 20 minutes directly onto the roots of the plants, a method that saves water and makes sure the water is used efficiently.

He planted the hops — actually small pieces of hop root clippings sold by hops farmers — on April 15 and, as they grow, the young vines wrap themselves around vertical ropes on the trellis system, with a little assistance from Weirback.

The most difficult times were early on, Weirback says. ”The weeding was the worst. We were out here pulling weeds on both days of every weekend. It was backbreaking work.” Next year, he plans to mulch the plant rows early in the growing season, keeping the weeds down.

Hops is a weed of sorts and once the plants produce mature ”cones,” as the hop flower or fruit is called, farmers prune the plant at ground level. If conditions are right, the plant returns next year, stronger and bushier than the previous year. A properly maintained hop plant can live for 30 or 40 years.

Weirback isn’t sure how large the harvest will be from his first-year plot. Judging by the number of flowering hops plants, he suspects he’ll have enough to make a batch or two of fresh-hop ale, typically called harvest ale.

”This is something brewers have been doing for three or four years,” says Weirback, standing among the rows of Nugget hops, which have taken off faster than the rows of Centennial at the other end of the plot. ”You have to make the beer within two days of picking the hops. You get this fresh, aromatic flavor out of the [fresh] hops,” he says. ” There is a lot of interest in IPAs [India pale ales] and hoppy beers and this is a new angle on it — a fresher flavor. They’ve proven pretty popular in the industry and this gives us a way to ease into the [hops] business without having to deal with all the equipment at once.”

tim.blangger@mcall.com

610-820-6722

Copyright © 2008, The Morning Call